For too long now, artists who haven’t met the criteria of being pale, male and stale have been excluded from art’s history and institutions. If art takes life and presents it back to us, we must have a very limited worldview, given the conveyor belt of Matisse and Picasso, Hirst and Koons that we’re so used to seeing. Make no mistake, though – artists outside of this standardised mould have always existed and worked. Now, thankfully, the likes of gal-dem, Two Brown Girls and Variant Space are shining a light on the work of BME women artists.

A new exhibition, We Are Here: British BME Women, seeks to explore what it means to be British and BME today. Organised and curated by Erin Aniker, Joy Miessi, Ellen Morrison and Jess Nash, the group show will display works from 15 artists, showcasing their response to and interpretation of two identities that are often assumed to be mutually exclusive. The exhibition seems particularly poignant right now, given the current anti-immigration rhetoric, our decision to leave the EU, and the rise of white supremacy exacerbating divisions within the UK.

From Danika Magdelena’s candid portraits to Sofia Niazi’s intimate illustrations, the exhibition hosts some of the most exciting creative talents in London right now. Alongside the show, there will be a panel talk with the artists and a workshop inspired by Nefertiti; it’s set to be a huge success. We spoke to four of the artists about their craft, what being BME and British today means to them, and what they wish people would stop asking them. Click ahead to read their stories.

We Are Here: British BME Women

Alev Lenz Studio, 73 Kingsland Road, E2 8AG

Private view: 6th July 2017

Exhibition continues: 7th-9th July 2017

Leyla Reynolds, head of illustration at gal-dem

How did you first get into making art?

During university I went through various bouts of poor mental health, as well as general frustration and, to be frank, exhaustion at the establishment nature of politics in this country. Making art started off as an outlet and a vehicle for setting the world to rights. I've always felt that art is an important act of protest. When you look at the context of BME artists in this country, the very nature of our history is political, the black arts movement – Donald Rodney, Ingrid Pollard, Keith Piper – we come from politicised circumstances, our whole existence is political.

Tell me a bit about the themes in your work.

I like to think of my works as gargoyles – they're ugly caricatures and when you look at the subjects, it becomes apparent why. I like the drawing style to speak for itself and betray an inherent critique of the characters depicted. I often draw on old propaganda posters when referencing modern-day political circumstances. There is a lot that can be gleaned when looking at the rhetoric of the past in comparison to now, so many of the same verbal tropes are still applied when trying to convince a larger number of people that your ideology, way of living, is the best.

Who are your main artistic influences?

Václav Chad, Donald Rodney, Wolfgang Tillmans, Ian Kittredge, Hannah Buckman and Fran Caballero.

What impact has the post-Brexit anti-immigration rhetoric had on you as an artist?

It's made my work more angry for sure – there's a sense that what we were experiencing already has been heightened. Make no mistake, anti-immigration, anti-PoC rhetoric has always been widespread and BME people have always been aware of it, but it's never been so seemingly mandated by the press and by the public. In terms of my work, I don't feel like it's made a huge amount of difference, my identity as a body which is continually othered, continually questioned and analysed as to my level of belonging, 'assimilation', proximity to Britishness continues to influence my artistic responses. These are all themes that BME people experience on the daily and will continue to experience, if just to a heightened extent, post this unnecessary referendum.

What does it mean to you being a BME woman living in Britain today?

The cuts under the last seven years of Tory governance have meant being a woman and a BME woman in this country is dangerous. Black, brown and migrant women face a higher risk of homicide in the home with hostile immigration control exacerbating this by blocking access to refuge. Sisters Uncut report that Women’s Aid statistics show that two in three women who approach refuges for help are now being turned away and that for BME women, that figure rises to four in five. Being a BME woman in Britain is solidarity – our humanity is constantly questioned and threatened – but organisations like Sisters Uncut and like gal-dem are working to fight back on all levels.

What does your dual British/ BME identity mean to you?

Despite being subjected to a constant state of unsettlement, where you never know how you're going to be perceived as a woman of colour in the UK, I feel like it has enabled me to feel a connection or discover a sense of ownership of cultures that I might not have met with. I find it interesting that we'd say 'dual' as if the two were mutually exclusive because I've never thought of them as being so. I'm British and I'm 'BME' and that shouldn't be unusual.

What is something you wish people would stop assuming, asking or thinking of you?

I'm just tired of being asked where I'm from all the goddamn time. There's only so many times you can glare back and answer 'England'. It's such a disrespectful way to point out that I'm not white, because that's all they're asking really, 'Why aren't you white?'

What do you hope this exhibition achieves?

To re-emphasise that to be a woman of colour is to exist in a broad church. We're a talented, determined and varied bunch of people.

Nasreen Shaikh Jamal Al-Lail, artist and cofounder of Variant Space Collective

How did you first get into making art?

I know it’s a cliché and a lot of artists say that they use art as a means of expression, but art really was the easiest method of expression for me. I’m dyslexic so instead of writing things down I found that I could easily convey my thoughts through art and photography.

Tell me a bit about the themes in your work.

My work is very autobiographical and so it’s constantly changing, depending on who I am and what I’m experiencing. My work is very much about exploring my journey as a person – I’m always in-between the UK and Makkah, and my work shows that duality.

And why you choose to work with the material you do...

All of my work starts off as a photograph. I sometimes use video or apply paint or mixed media directly onto the photographic prints. I often find myself experimenting with ways of disturbing and damaging the original photographs by adding in layers of mixed media such as oil pastels on top.

Who are your main artistic influences?

As the curator and cofounder of Variant Spaces Collective, I take inspiration from online curatorial platforms such as The Jealous Curator and Design Milk. I’m also very inspired by the aesthetics behind a lot of Japanese and Korean cinema.

Has your style stayed the same or has it slowly developed?

It has developed quite slowly; my current work definitely feels more developed now than ever. I’ve found that the more I get to know myself, as a woman, the more confident I am with myself and my work. I’m able to let go of and shed my previous insecurities and I’ve found that process of transformation quite important in my current work, which feels more confident and uplifting. The more I go back to Saudi and Makkah, the more spiritual I feel and I think this comes across in my work. My work now feels like it has more direction and purpose.

What impact has the post-Brexit anti-immigration rhetoric had on you as an artist?

I think it's highlighted the fact that we’d assumed people were moving into a general direction of acceptance, but we’d mistaken this acceptance for simply tolerance. We weren’t being accepted, we were being tolerated. Brexit brought that to light. It led me to further push my collective, Variant Space, providing a platform for Muslim women in art, and we actually have an exhibition on until September at Oval Space in Vauxhall, fuelled by this anti-immigration rhetoric, showcasing Muslim women artists from around the world.

What does it mean to you being a BME woman living in Britain today?

Being a veiled woman of colour automatically comes with a large amount of racial prejudice in Britain. The media’s portrayal of Muslims and Muslim women make it very difficult to live in Britain. In general, most local communities are very supportive but there are always certain individuals who regularly come out with racist and Islamophobic rhetoric and actions. I want to be at the forefront of veiled, Muslim women of colour actively resisting these stereotypes, but at the same time I have to be wary of being attacked and targeted because of the way I look.

What does your dual British/ BME identity mean to you?

I moved to the UK when I was 9 years old from Makkah and I go back there a lot. So for me, I have this perspective of calling two very different places and cultures home. I want people to be aware that having a dual BME identity doesn’t mean that you have to pick or prefer one, it’s not a case of the grass is greener on the other side. It’s about having more balance and perspective about both of your cultures and backgrounds.

What is something you wish people would stop assuming, asking or thinking of you?

It’s basically for people to stop assuming that my family forced me to be a veiled woman, for people to stop asking if my religion promotes violence, for people to stop thinking of me as a victim. My religion does not promote any of this, my family support me entirely in all my decisions and these are my decisions. These assumptions of Muslim women as victims have been created and are perpetuated today by the media. People need to wake up and start looking at women for who they are, through their voices and actions, not through their looks or their choice to wear a veil.

What do you hope this exhibition achieves?

To enrich people with different narratives to see the complexities and layers there are in simply being a human being. I’m from Saudi, I was brought up in the UK and my mum’s from India. I speak three different languages. Human beings are complex, we can’t box people into one simple narrative.

Erin Aniker, illustrator and visual arts editor at The F Word

How did you first get into making art?

I grew up completely obsessed with illustrations in '90s children’s books, and also the shapes and patterns found in Turkish ceramics and textiles. Not much has changed since then, to be honest.

Tell me a bit about the themes in your work.

I struggled with issues of mental health when I was younger and was privileged and lucky enough to be supported by a team of strong, inspiring women around me at the time. I am constantly inspired by these women and find myself constantly meeting new, incredible women every day. My work explores these notions of sisterhood, strength, female solidarity and support.

And why you choose to work with the material you do...

Most of my work is completed digitally using a tablet on Illustrator. I enjoy the clean finish of digital illustration and the variety of brushes, materials and textures readily available. I love the infinite possibilities working digitally allows you – you can never really and truly ‘finish’ a piece. I complete all my initial work using pencil and pens in sketchbook and have also recently started experimenting with illustrated ceramics. Ceramics help me to create work in a completely different vein that’s more tactile and also allows me to escape from screens for a few hours a week.

Who are your main artistic influences?

Frida Kahlo, Manjit Thapp, Betty Woodman, Laura Callaghan, Chris Ofili and Wolfgang Tillmans. I have also been obsessively reading anything by Elif Şafak and Orhan Pamuk.

Has your style stayed the same or has it slowly developed?

It’s developed pretty rapidly in the last two years since graduating. I was exposed to a range of literature and research around intersectional feminism at university and I was exploring how to convey this visually for some time. I actually only learnt how to use Illustrator software and work digitally in the last couple months of my illustration degree in my final year, so my style and practice is still developing now.

What impact has the post-Brexit anti-immigration rhetoric had on you as an artist?

The post-Brexit anti-immigration rhetoric essentially fuelled me into bringing this exhibition into existence, with the help of some incredibly talented artists and creatives. We plan on applying for funding after this exhibition so we can hopefully make it a touring project around the UK, working with other BME women artists in Britain. There are more exhibitions, workshops, panel discussions and events which need to be held so we can say, across Britain, 'We Are Here'.

What does it mean to you being a BME woman living in Britain today?

Being half-Turkish, half-English and white-passing comes with a lot of privilege that many other BME women don’t have. I think this comes with a greater responsibility to use this privilege to support BME women who experience issues around colourism and racism. I feel a strong sense of solidarity with other BME Women, and platforms such as gal-dem, Media Diversified, Skin Deep magazine, Sisters Uncut, Femini magazine and The F Word are just a few that are fighting to make sure BME women’s voices are being heard.

What does your dual British/ BME identity mean to you?

I’ve always had a constant feeling of displacement between my Turkish and English sides, and not completely identifying with either culture can leave you feeling quite alienated from both. I think this can be a positive as you find your own sense of identity and confidence by relating to both identities in your own way and on your own terms. Especially living in a city like London where there is a mix of so many different cultures – I’m proud to be a Londoner, to be British, and to be from two very different cultures. I think it can be deeply problematic when you make these two identities, British and BME, appear as if they are mutually exclusive.

What is something you wish people would stop assuming, asking or thinking of you?

‘Yeah but where are your parents from?’

What do you hope this exhibition achieves?

To encourage more BME women to be proud of, publicly celebrate, explore and acknowledge your heritage. That migration and freedom of movement is a basic human right. That artists and people from all backgrounds and cultures living together make life and daily interactions so much more meaningful, interesting and rich. That we, British BME women, are here. Though this exhibition only showcases a small handful of artists, I hope this inspires more BME women to become more active in organising exhibitions, talks, meetings and events. The handful of British BME women in this exhibition are here, making art and moving up.

Joy Miessi, artist in residence at LimeWharf

How did you first get into making art?

My uncle had bought me art sets for Christmas several years in a row. I told stories with drawings and got into stop-motion animation and drawing faces. It’s always been the thing I’ve occupied myself with outside of school, university and work.

Tell me a bit about the themes in your work.

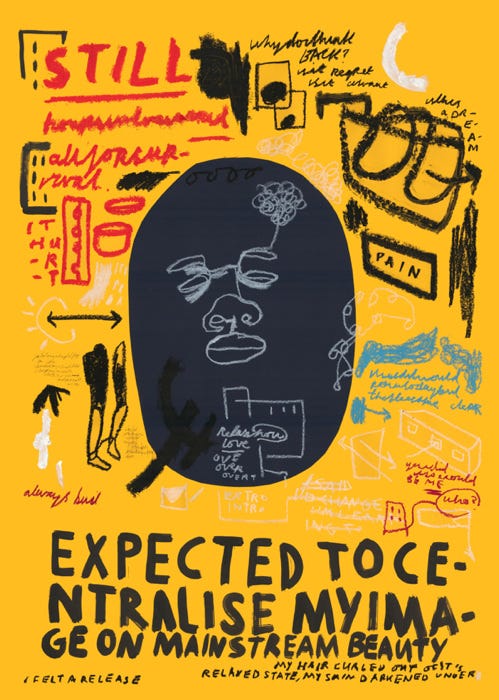

My work is a reflection of me: I make art about my blackness, my gender, my sexuality and my day-to-day life. My artwork is just like a person's diary. It tells my story.

Why do you choose to work with the material you do?

I love mark-making and any material that I can use with fluidity. Inks are one of my favourites to use but I also use oil bars, pastels, pencils and anything that will leave a mark and that is easy to write with. For the base, I use scrap pieces of paper that I’ve saved, from bus tickets to cardboard. It’s a low-cost way of sourcing materials and adds texture and a whole new layer to the piece.

Who are your main artistic influences?

Kara Walker, Jenny Holzer's text pieces and Matisse’s cut-outs. These artists, alongside many poets, writers and musicians, have stuck with me as constant inspiration since college.

What impact has the post-Brexit anti-immigration rhetoric had on you as an artist?

It has affected my family, people I know and how black/brown British people are responded to, even passive-aggressively in certain environments. These day-to-day moments and feelings find their way into my work as I document the now, through drawings and text.

What does it mean to you being a BME woman living in Britain today?

To me, it is visibility and invisibility. As a black British woman, our narratives are often left out of the media, the misogynoir we face isn’t taken seriously – think of Diane Abbott. Yet, to me it also means visibility: the stares, strangers touching our hair, being followed by security, etc – sometimes it feels like you can’t just be.

What does your dual British/ BME identity mean to you?

Displacement and also pride. In Congo, many assumed I was a tourist and in the UK many have assumed I am from here. So I’ve often wondered where I belong but despite this, I love London and I love Congo and I take pride in having these places as home.

What is one thing you wish people would stop assuming, asking or thinking of you?

If they can touch my hair. Solange’s song “Don’t Touch My Hair” comes to mind, as it perfectly translates the feelings and frustrations of this action.

What do you hope this exhibition achieves?

I hope that many see this exhibition, hopefully find out about a new artist and realise that we, BME women, are out here: we are making and creating waves. We don’t want to only be considered as a last-minute choice to diversify a line-up or only be selected for a black history month event, etc. We are out here all year round, making art for ourselves and challenging the image of a whitewashed art world. The exhibition only highlights a few artists, but I hope it also encourages other BME artists to start up their own exhibition, collaborate and keep making art, to be the representation you want to see.

Like what you see? How about some more R29 goodness, right here?

If You've Ever Been In A Texting Relationship, This Novel Is For You